Written by Eric Grant

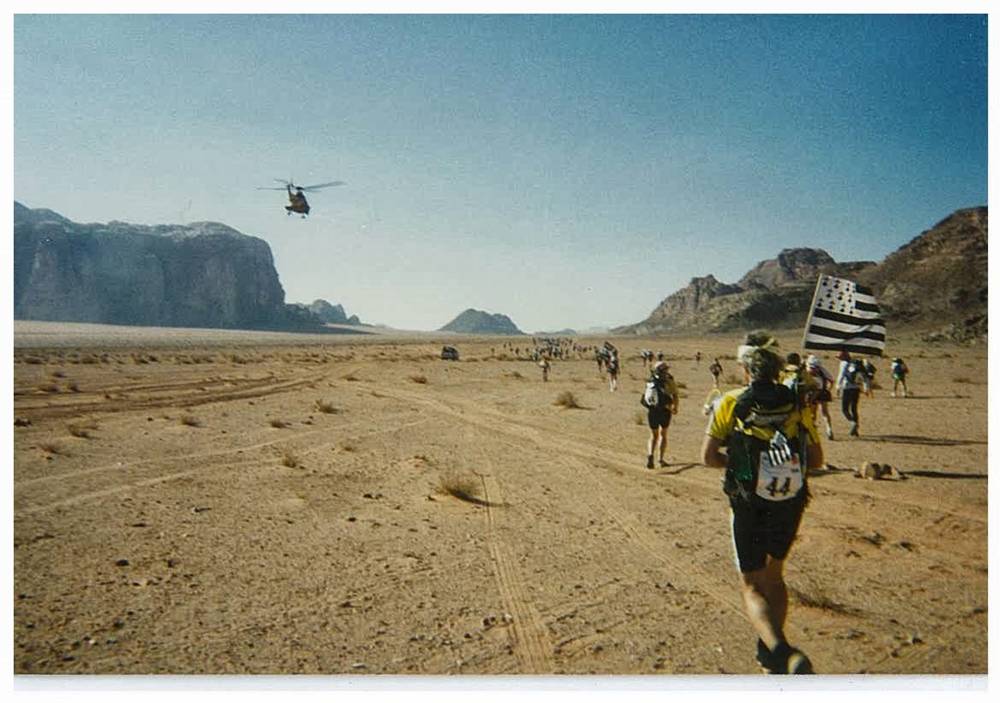

After jogging at a decent clip for the first 20 miles, then alternating running and walking for the next 20, I arrive at nightfall in decent condition (considering that the first 100km or 65 miles are all soft sand). I warm up some water and enjoy a meal of freeze-dried risotto, before heading back into the night. The heat of the day—merciful compared to the Marathon des Sables but still in the low nineties (Fahrenheit)—has given way to a pleasant nighttime cool. At the same time, I will no longer be spurred on by an incredible reddish landscape of canyons, cliffs, caves and arches that remind me of the Grand Canyon.

Until now the first four or five checkpoints basically consisted of a Land Rover or two around a campfire and a ramshackle medical tent—tarpaulin stretched over four posts—for those in need. They are only a 160 or so of us at this first official edition of the Jordan Desert Cup. At midnight, however, I stumble across a much larger checkpoint offering the comfort of a closed tent for people to stretch out their sleeping bags. My body is too charged with adrenaline to stop and sleep, so I continue into the night.

Four hours later, I find myself lost. I realize this about ten miles after passing the Hedjaz railway line. I remember the railway because I stubbed my toe on the sand-covered tracks at 4am. (The Hedjaz railway is famous for having suffered attacks by Lawrence of Arabia in 1917-1918. It says so in my roadbook. Or perhaps someone told me. The start of the race was twenty hours ago and it’s now a bit of a blur.)

I stubbed my toe because I’m not wearing my headlamp. I’ve always liked the semi-darkness, the tantalizing shadows, the promise of forgetting reality far from the glaring sun. So I turned off my lamp to enjoy the full moon and the Milky Way—the first time in a decade probably that I’ve actually seen the Milky Way stretch across the heavens like a spotted freeway. You don’t see many stars in Los Angeles.

Then the full moon scampered off with the approach of dawn, the stars bid farewell, and I was too tired even to notice that I couldn’t see where I was going.

“I’m lost,” I say to myself without actually drawing any conclusions from that statement or devising any plan of action. As if somehow I will stop being lost if I simply acknowledge the fact and wait long enough for the aggravation to pass.

I drink lukewarm water from the liter-and-a-half bottle I received at the previous checkpoint, and refuse to panic.

I’ve been awake now for almost twenty-four hours, and running, slipping and stumbling through the sand for just over twenty. I should know better than to trust my eyesight; I can hardly trust my mind. I’m in a state of… hmm, how to put it? It’s like when you’re out in the cow fields and you swallow those first few psilocybin mushrooms: not quite enough for a full-blown trip, but just right to spot all the others among the cow dung and the weeds.

Okay, perhaps that’s not the best metaphor—what I’m trying to say is that I realize ten minutes later that I am not heading toward a glow stick marking the trail or another runner’s headlamp. No, what I saw as my saving grace was a lamppost. A bloody lamppost.

Which makes me wonder: what is a lamppost doing in the middle of a desert?

After another twenty minutes I arrive at a paved road that cuts across the desert heading north and I know that I am off track.

That, in itself, is not a problem—how far off track is the essential question. How many miles will I have to add to this already inhumanely long race?

My body is strangely electric from lack of sleep and pushing myself beyond several layers of limits—this is only my second ultra and third race since I started running 18 months ago—and I now sense Panic raising its knobby head without any way to keep it at bay. Covering 100 miles on foot is one thing, but getting lost in the desert?...

I am standing on the side of a road, the presence of which, if I bother to think about it at all, makes no sense. I can’t get my mind off this: I’m supposed to be in the middle of the Wadi Rum desert, making my way to the ancient Nabatean city of Petra, and there shouldn’t be a bloody road!

Hitchhiking is not an option. Besides the fact that there are no cars at this hour, it would mean dropping out of the race—and that will not do. Certainly not. Not yet anyway. I’m not ready for that. The 100-kilometer (65-mile) marker should be coming up soon according to my road book, and so will dawn according to my watch, and I don’t want to miss either. I haven’t seen the sun rise after a sleepless night without artificial stimulation for a very long time, and I’ve certainly never run/walked 100 kilometers non-stop in my life.

My mind is a sieve. I feel like David Bowie looks in the movie The Man Who Fell to Earth.

Thankfully there is the landscape, the beauty of nature, the marvel of life, and the occasional sequence of moments suffused with euphoria when I am utterly in the present.

The advantage in my current situation of being lost is that I have no sense of pain. My legs are like blocks of molten rock, disconnected from my body—but otherwise I am strangely electrified. Just as the reality of my predicament is starting to sink in and I begin to wonder if I won’t actually have to quit the race because I’m lost, I notice three bobbing lights in the distance, perhaps a half a mile off to my right: glow sticks hanging off three participants’ backpacks!

This time I am sure. No street lamps.

I cross the road and head in their general direction. I lose sight of them, but I quickly come across a dirt track and a sign post placed by the organization and lit by a cylume stick—I am back in business.

I start jogging, pumped with endorphins and adrenalin, energized by finding my way again and with the approach of dawn. The purple haze of the sky lightens to a tabasco-stained cerulean blue. I wish I could embed the image on my memory forever.

Morning breaks fully by the time I reach the 100-kilometer marker. I take a picture of myself, haggard and wide-eyed—something to look back on, to remind myself that I was actually there... Here... Wherever this is. (And now I can no longer find the picture taken with a disposable 35mm camera).

I pass another milestone at 8am: I have now been in this race for 24 hours. Kilometer 110 (mile 69), or thereabouts.

I come across a rudimentary tent set up by the organization. Basically canvas stretched over four poles, where runners can rest out of the sun before starting up the long stretch that leads to the next check point: nine miles and several thousand feet up a dirt road that winds its way around what looks like a mix between canyon and quarry. Nine long miles.

Blissfully, however, this marks the definitive end of the soft, loose sand that has been our lot since the beginning of the race. According to the road book, nothing but packed gravel, stone and mountain paths.

I’m all alone.

I sit down, take out my portable stove—a small metallic box the size of a cigarette pack that opens upwards to make space for a fuel table. I heat some water and enjoy a bowl of freeze-dried pasta—something approaching “real food”. I’ve varied my nutrition for the Desert Cup after my experience in Morocco: I have beef jerky, mixed nuts, even cheese in sealed packages. Dry roasted peanuts, my favorite.

I finish breakfast, pack everything away, and head up towards the Rift plateau and checkpoint 10. Or 11. I’ve lost count.

I hear shuffling steps behind me as I my make my way through the canyon, and am soon joined by a lawyer from Geneva whom I met at the recent Marathon des Sables. He is jogging at decent clip and I wonder why he was behind me, until he tells me that he slept for four hours. Evidently it did him a world of good, because I cannot keep up with him and am forced to slow my pace to a walk.

“Hard to tell,” he says when I ask him how he feels. “Both empty and fulfilled.”

As he charges off into the distance, I’m feeling rather more empty than fulfilled. My spirits are sinking rapidly and my mind starts mulling dangerous thoughts. The heat has risen progressively since dawn to a sweltering 95°F and the next aid station has been visible in the distance since I started the climb—but, like a mirage, never seeming to get any closer. The only positive factor is the relief of being on solid ground after sixty miles—a day and a night—of soft, sugary-like sand, with the feet sinking at every step.

I stop and sit down every 500 yards or so. I know this can’t be a good idea—and certainly I can’t expect to cover another 40 miles at this rate—but my legs hurt at every step. I’m beginning to think that I won’t finish. Perhaps I’ll pack it in at the next checkpoint... 75 miles is still quite an accomplishment.

I’m not sure I even want to keep going. I never considered the Marathon des Sables to be cruel despite the hardships—but the Desert Cup is definitely taking on the air of an outdoor torture chamber for masochists.

I keep telling myself, “Wait until the next aid station, wait till the next aid station”. No use making rash decisions—even if I quit, I still have to make to the next aid station… I’m beginning to refuse reality: I don’t have a choice, I can’t stop in the middle of nowhere; yet I can’t imagine facing the two, three, four hours it will take to get there… That’s entering torture territory right there.

Salvation appears in the form of a whistling Italian doctor. I quickly latch on him, struggling to maintain his pace. But I manage to do so, the mind and will once again taking over the body.

We speak of desultory subjects, the miles slip away and we finally reach the end of this interminable winding road and summit the Rift at 11am, Wednesday 8 November.

(The thought briefly crosses my mind that the United States should by now have elected a new president: Bush or Gore?)

Incredible: the panoramic view of the Jordan valley in the shimmering sun, of course; but also, and especially at this point, the mattresses laid out by the organization under a sturdily built open-flap tent.

I don’t move for two hours. I don’t want to move. I can’t sleep but I just can’t move. Exhaustion has put me in a trance, and I feel electrified and exhausted at the same time. But don’t ask me to move. The only thing I do is change my socks, rotating again with the two other pairs I have: one dry in my bag, one hanging off my bag drying. The strategy worked at the MDS and here too, even after more than 70 miles of stumbling through the desert, I have no blisters, or nothing worth worrying about. One addition from Morocco are the gaiters which I had sewn into the soles of my shoes. The same trusty shoes.

Otherwise I just sit there, for two hours, my brain void of all thoughts; if it were a heart, it would be beating at the rate of ten a minute. My body refuses to go anywhere. I realize that I am well within the cut-off time—I have over 30 hours to cover the next 30 miles—and suddenly I know, just know,that I will finish. I know I will keep going to the bitter end. I just don’t know how or what it will cost me. But I am strangely elated. Is this what it means to be zen?

I don’t want to move because the peace I felt after completing the long stage of the Marathon des Sables pales in comparison with what I am experiencing now.

Who knows how long I would have stayed if a sympathetic French mountaineer, Thierry, hadn’t urged me to join him. After two hours, I can finally consider leaving. Or, as he says: “If you don’t leave now, you will end up by dropping out.” So I get up, refreshed, and embark on the 1,000-foot climb along the Rift—and the final 27 miles before the finish line.

After 30 hours of quasi-solitude, it is nice to have company. Actually, “nice” is really not the right word. It turns out that Thierry’s presence is essential. The serenity that filled me at the check point dissipates within a few miles of renewed power walking, and I realize not only the distance still left to cover, which seemed so accessible when I was resting, but also and mainly the time it will take me to cover it. Having a fellow traveler at my side allows me to forget this for a while.

I learn that Thierry has summited the highest peaks on five continents—only Everest and Mount Vinson in Antarctica are missing from his accomplishments—and I can’t help feeling just a little proud to be so far into the race moving along at his speed.

We cover 20 miles together. The landscape has changed from the pure desert of the first sixty-five miles to the mountainous décor of the Rift. Soon we’re even passing through agricultural land dotted with houses.

Shortly before nightfall (nighttime again!) we add a layer of clothes. The temperature has plunged below 50°F, with the wind chill factor making it feel like it is near-freezing.

We reach the next check point as the sun sets, but soon realize that it is pointless to try and cook anything as the wind is blowing in gusts of up to 65mph. I’m forced to add cold water to my freeze-dried chili—obviously it doesn’t mix, and I’m left with crunchy water with chunks of flavorless goo that amazingly doesn’t upset my stomach more than it already is. Leg fatigue I can deal with; stomach problems will drain me of all energy.

Thierry and I follow a gravel path lined with large boulders, through rolling hills spotted with villages and disparate lights. My tired mind plays tricks on me—at every turn in the road, I see figures emerge from the ground like ghosts rising from a graveyard. I even imagine a cable car stretching across the valley. Thierry pokes gentle fun at me, until he mistakes our hobbling shadows for two massive scorpions. We collapse in fits of hysterics.

Though I have no thoughts of quitting, each step is becoming increasingly agonizing. My shins feel like they are on fire, and soon I have to stop every three hundred yards or so to sit down for a minute. So much for dealing with leg pain...

As intense as my suffering may be, however, it seems inconceivable not to finish. I am only eight miles away. One step at time... Never has this common cliché been so true. Thierry sticks with me throughout, shores up my flagging confidence, slows his own pace to match my own, waits every time I stop. Without Thierry, I doubt I would have finished; yet several years later, I will almost have forgotten his name.

We reach the modern city of Petra: a mile to cross it, then we will make the long descent into the ancient Nabatean city.

First we stop at the Hotel Movenpick Resort Petra. We’re not asking for anything in particular, we have no money in any case. We just want a taste of upscale comfort after nearly 40 hours in the desert. How strange, since part of my reason for competing in a race such as the Desert Cup is to distance myself from the comforts and consumerism of society…

Ah, then I realize that actually I am reveling in this sense of contentment comes from deep within me, and has nothing to do with these cushy armchairs on which I fart discreetly.

I’m not sure what effect our spectral appearance has on the hotel guests. There aren’t many—it is nearing midnight—and the hotel manager, bless him, graces us with a smile instead of kicking us out. And here I was thinking we would have to defend our reasons for stopping in his hotel.

Indeed, we have a purpose beyond enjoying a few moments in the hotel lobby away from the wind and cold: we hope to use the bathroom—the comfort of a porcelain toilet rather than squatting in the desert with sand up our asses and wiping ourselves with pages of our road book.

Having settled that matter, I let Thierry go on without me. He’s in far less pain, and with only six miles to go I’ll be fine. Still, I stop at the final check point. The wind has blown away the tent and there is only a Land Rover and a lone representative of the organization to mark the spot. I collapse in the passenger seat of the Land Rover, pop an anti-inflammatory pill, and pass out for twenty minutes.

I wake up feeling manic for some reason. After 40 hours, I am desperate to finish. I check the dashboard: it’s half past midnight.

The wind has dropped and I charge across the plateau and head down the massive 800+ steps that descend into ancient Petra—before realizing that I’ve forgotten my headlamp in the Land Rover.

No matter. The moon lights up the sky like a Hollywood film set, and I climb rather than walk down the steps, careful not to stumble at the last moment. When I reach the bottom—still hallucinating as I see glass scaffolding all along the canyon walls: the moon reflecting off the rocks—I find the way lit by candles.

I shuffle along marveling at this rose-red city built 2,000 years ago, rediscovered in 1812 by a Swiss explorer, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt. I pass the Treasury Temple, the setting for Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, feeling like the first and last person on earth, thinking that no running or travel experience will ever supersede this one: walking alone through candle-lit Petra at two o’clock in the morning.

My father congratulates me the next morning at breakfast—with the news that the US elections are still in the balance due to a recount in Florida.