Written by Christian Maleedy - https://runningchristian.wordpress.com

It is almost 4pm on Saturday and I have just arrived at Arnouvaz in Valle d’Aosta in the Italian Alps. This is the 95.6km checkpoint in the UTMB. The last few muddy miles of descent have left me reeling. I know what is coming next – the ascent to the highest point on the course, Grand Col Ferrett at 2,529 meters. I have no idea how on earth I am going to manage it. As I walk into the Checkpoint, there is a desk marked as “abandonment”. I want more than anything to walk over to that desk, hand over my race number and declare “Oui, oui, oui, abandonment, s’il vous plait”. Within minutes I would be sitting, dozing on a warm minibus waiting to taken back to Chamonix. But something inside won’t let me do that. I may be cold, fatigued and achy but I’m not injured and I still have a reasonable margin on the cut offs. My family and I have sacrificed so much to put me on the start line of this race and to give me the opportunity to achieve my dream of completing the UTMB. Would I really throw that away now because I’m a bit cold and a bit sleepy?

Part one – France to Italy

A little over 22 hours earlier and I’m standing on the start line of the Ultra Trail Du Mont Blanc in Chamonix. This race has been joint top of my bucket list (along with Western States 100) for several years. Standing alongside 2,500 runners, I reflect back on the last few years of running and how each of my successes and failures has led me here to this. Every successful race has boosted my confidence enough to make me believe that I am good enough to be on the start line of the UTMB, and every failure has taught me a valuable lesson that I would need to reach the finish line.

Above us, the flags from the dozens of nations competing flutter gently in the alpine breeze like prayer flags on Everest. A massive sense of excitement and expectation sits over the crowd; runners and spectators alike. My mouth is dry from the nerves and I take a swig of water from bottle. It doesn’t help in the slightest.

As has become tradition, the race always begins with Vangelis’ “Conquest of Paradise”. A hush falls over the waiting runners as the first few eerie bars of the piece drift from the speakers. Soon, the air is filled with the sound of Gregorian chanting. Just as Vangelis’ trademark synthesizers kick in and the track reaches its soaring crescendo, someone shouts “Go!” and we are off.

Running through the streets of Chamonix, I high-five as many of the cheering spectators as I can. The inspiring music and the cheers from the crowd form a heady mix and I know this moment will be one that I won’t ever forget. I wave to Caroline and the boys who are waiting in the crowd a few hundred metres from the start. All being well, I will see them the following day in Courmayeur.

The pace in these early couple of miles is frantic – probably close to 7 min/miles. For me this is suicide pace for anything other than a Saturday morning parkrun, let along a 100+ mile mountain race. However, I’m not too concerned for now.

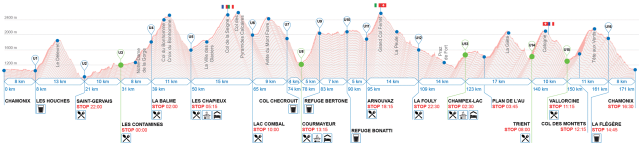

I’d thought a lot about strategy prior to this race. The UTMB is 104 or so miles long, beginning in Chamonix and traversing the French, Italian and Swiss alps before returning to France and finishing in Chamonix.

I knew that (apart from injuries or something unforseen) there was only one thing that could realistically prevent me finishing this race and that was the cut-offs. There is an overall 46 hour limit to compete the 104 miles and there are many points along the way that have intermediate cut-off times. Miss these, even by a few seconds, and my race would be over. Being familiar with my own strengths and weaknesses as a runner, I knew my best bet would be to go out hard, try to build as much of a buffer against the early cut-offs as possible and then just hope that buffer is enough later on to get me to the finish when things get tough. The strategy is not without risk as, of course, there is the possibility of blow-ups late on, but it is the strategy that I have chosen and it’s what I’m going with.

The air is cool and at present, fairly ideal for running. Over the past week, there has been all kinds of speculation about the weather and whether any amendments to the “normal” route would be needed. The forecast is for snow and -9 degree temperatures above 2,000 metres. Eventually the organisers confirmed it would be the normal route but with two small amendments. I believe the difference is negligible in terms of actual distance but it is a little less climbing. The quid pro quo is that we have 30 minutes less in which to complete the route.

As we leave the paved streets of Chamonix behind, the advice of me good friend, Tim, rings in my ears “push up as far as you can until you see runners who are well out of your league”. I take a look around me; mission accomplished as far as that goes. The first few miles of the race are the only significant flat part of the course and I intend to make the most of them. I know that I will be hemorraging time later on the climbs. I may have a chance to make some time back on the descents depending on how technical they are – but that means that anything approximating “flat” needs to be run and run at a good pace, or I will be timed out of the race for sure.

Of course, this section is only “flat” by alpine standards and would be “undulating” in the UK. We are now on green woody trails and I’m surprised by how far spectators have come out from town to cheer us on. Below to my left, L’Arve continues its tumultuous flow through the Chamonix valley completely oblivious to the runners alongside it. For some reason the sound of the river reminds me of Enya’s “Orinoco Flow”, her great tribute to travelling and adventure. But I’m in an adventure of my own here. I look up, surprised by the deep sound of an Alphorn being played by a spectator in traditional alpine dress. It is in stark contrast to the tinkling sound of the cowbells that would be our almost constant companion throughout the race.

The course continues along narrow wooded trails before opening out onto a wide road into Les Houches. For a moment, the running on the wide roads with so many runners around takes me back to Comrades in South Africa. Comrades is an amazing experience but this race is something else again. Running through the centre of Les Houches, we pass our first drinks station. The fast start meant that I’d got through one of my water bottles which I refill here and sip some coke before continuing on my way. Before long, we leave the road and began the first real climb of the course.

In my mind, UTMB is characterised by ten big climbs, with a cumulative elevation gain/loss of 10,000 metres. This is more than going from sea-level to the summit of Everest and back down again, whilst running four back to back marathons. I decide this analogy isn’t helping me. Instead I think of the race as 10 ascents of Snowdon. A few weeks previously I’d spent a weekend training on Snowdon, ascending and descending via the six main routes. Everest feels out of my league, but 10 Snowdons somehow feels more attainable!

This first climb up to Le Delevret is 820 metres of ascent, but on fresh legs feels reasonable. There is a crowd of us and the air is filed with the clickety sounds of hiking poles on the rocky terrain. My poles are still firmly attached to my back as I’d decided in advance to attempt the first climb without them. Instead, I lean forward, put my hands on my knees and push up the mountain.

This is a ski resort in winter and we climb beneath the chair lifts that would transport the skiers up the mountain in the winter. Before long, the incline begins to flatten. Could we be at the top? I round a corner and the bottom of another chair lift comes into view – nowhere near the top yet! As we ascend higher the fog and darkness begin to envelop us. On finally reaching the top, visibility is severely reduced. I get my headtorch out. However, in the thick fog, the beam of light only serves to light up the air particles and I can see very little beyond a metre or two.

The descent is initially on steep, wet grassy banks which I tackle tentatively at first. My fellow runners are flying past me on both sides and I decide to throw caution to the wind and pick up my pace. Before long, the steep grassy section ends and we are on much more runnable switch backs leading down into St Gervais. We are out of the clouds now and the lights of the town sparkle below us. We can hear the sounds of a street party in full swing below us, still a good couple of miles away.

Running into St Gervais, the roads are thronged with people who have come out to cheers us on. Cries of “allez, allez, allez” echo all along. Here is my first experience of a UTMB checkpoint. My usual experience of an ultra marathon aid station in the UK is a picnic table with a few sandwiches and cups of coke lined up. This is more like a food festival or farmers’ market with dozens of stalls set up offering all kinds of food and drink. I feel the first hunger pangs so I take some bread, cheese, salami and chocolate to eat as I walk out of St Gervais. A key part of successfully completing this race will be to continually eat throughout, ensuring there is a steady stream of calories going in.

The next section is undulating but reasonably runnable. I therefore stick to my strategy and run as much as I possibly can, only slowing to a hike for significant climbs. The food I ate at the last checkpoint isn’t sitting well and I start to feel slightly queasy. The thought of more cheese and salami during the race makes me feel ill – I will have a look what else is on offer at the next checkpoint. Some runners seem to be really suffering as I pass a few people throwing up by the side of the trail. Just another Friday night like back home in London town!

Les Contamines is the first major checkpoint where runners can have access to their crews. It’s also the first cut-off point along the race. The time is now 22.41 and the cut-off here is 00.30 – so far , so good. The Aid Station is set up as a massive marquee. Inside, it is absolutely rammed with runners and supporters. I find a spot on a bench to sit for a few minutes, before continuing on my way.

It has begun to rain and I put my jacket on, not wanting to get wet and cold so soon. Next is the first real test of the race; a climb of 1,342m up to Croix Du Bonhomme. As I begin the climb, I’m surprised again by the number of spectators who have also hiked up to watch. Bonfires, candles and oil lamps light the early section of this climb giving it a magical atmosphere, like something from Hans Christian Anderson. The flames hiss and splutter in the rain. Somewhere here out in the darkness is the baroque chapel of Notre Dame de la Gorge. However, it’s pitch dark and I can’t see it. Sightseeing will have to wait for another day.

We continue up the mountain. Far above me I can see the lights of the next checkpoint, La Balme. It doesn’t look very far but takes a while to get there. The main checkpoint is in a barn. My appetite for any more cheese and salami has completely gone but I gratefully slurp down two bowls of salty noodle soup. This would turn out to be a staple of every checkpoint and is probably the best thing I’ve ever had during a race. I take some chocolate to eat on the mountain and leave the checkpoint. “Ca va?” esquires one of the mountain rescue men who are ever present at the mountain checkpoints. I recall enough schoolboy French to be able to respond adequately and then continue on my way. Having a checkpoint half-way up the mountain really helps break the climb up.

However, whilst the first half passed quickly, the second half goes on and on. Several times, the trail begins to flatten and descend making me think that I’d reached the top, only for it to begin ascending again. I eventually forget about actually ever reaching the top and think of other things. At the top of the mountain, it is misty and cold and there is snow in the air. As we begin the descent, there is a volunteer checking our numbers and performing random checks of our compulsory kit. Thankfully (since it’s so cold) I’m not stopped and I continue along my way. The first part of the descent is on rutted, slippery grassy slopes. Try as I might, I can’t get any momentum going here which is frustrating as other runners are flying past. However, like the last descent, the track soon turns to runnable switch backs opening up the valley below us. I can see and hear the next checkpoint at Les Chapieux from a long way away.

On entering the checkpoint, the race officials are checking we all have a phone with us (part of the mandatory kit). I show them my phone and am ushered into the checkpoint.

I’m now 50km into the race, one marathon done and three more to go. I sit and enjoy some more of the noodle soup. Just as I’m about to leave, I hear someone call my name. It’s Sam Robson. I’d met Sam a couple of days previously as he has been staying in Les Contamines with my friend Tim. Sam is a far better runner than me and the fact that we are together definitely confirms the idea in my mind that I’ve gone out fast and probably a little beyond my abilities. We pass the next few miles together and it’s nice to have some company. We chat about people we know and races we’ve done and the first part of the climb passes quickly. After a while, Sam pushes on ahead and I continue up. I glance back and see a long stream of head torches proceeding in single file from Les Chapieux up the mountain side.

It is cold and snowy at the Col de la Seigne and I stop to put my gloves on. We have climbed another “Snowdon” since the last checkpoint and I am beginning to feel the effort in my legs. It’s almost 6am and I can see the first hint of morning light appear in the sky.

Ahead of me is the Col des Pyramides Calcaires. The first of the two route amendments for safety purposes means that we won’t be ascending this. I can’t say that I’m too devastated at the moment.

Italy to Switzerland

Somewhere on this dark mountain, I’ve crossed from France into Italy. As I begin my descent, the first rays of morning light illuminate the most incredible sight in front of me. A valley cut out of the mountains by glaciers many millions of years previously. Mountains that have been my companion for the last few hours in darkness, now revealed in all their splendour. Below me is Lac Combal the next checkpoint. This must be one of the most remote checkpoints in the race and I’m left wondering how they managed to transport all the supplies here. I sit and admire the views. Low lying clouds cover the nearby peaks – I’m reminded of the “tablecloth” that often covers Table Mountain in Cape Town.

As I’m sitting there, a volunteer holds up a pair of gloves – oh dear some poor runner has dropped their gloves. I touch my pocket where I’ve stashed mine only to realise they are gone. I gratefully retrieve them from the volunteer, it’s still cold and I’d be in trouble without them.

The course continues initially on a flat trail besides the remains of the lake before heading up towards the summit of Mt Favre. This climb is long and it is here that I start to feel the first real signs of fatigue. On eventually reaching the summit, I stop and lie on the grass for a few minutes, dozing a little and let the sun warm my face. We are now at an altitude of 2,434m. It is less than 10k to Courmayeur, the most significant checkpoint and the psychological “half-way” point in the race. However, it is also a descent of almost 1,500 metres to get there. The scenery here is stunning but I’m keen not to linger and enjoy it for too long. Around halfway between the Arrete Du Mont Fevre and Courmayeur is another checkpoint – a mountain refuge at Col Checrouit. It is marked on my course guide as simply a drinks point, but I’m delighted to see a lady outside serving pasta and tomato sauce from a giant pot – this is Italy after all!

After a brief stop here I continue down towards Courmayeur. The switch backs become steep and technical and snake through woods, teasing us with glimpses of the town below before we eventually arrive on the outskirts. I run through the streets, remembering to smile for the official photographer and arrive at the sports centre which serves as the checkpoint here. Carrie and the boys are waiting outside and I stop to talk to them briefly before continuing inside. It is one huge hall with an area for food, for sleeping, for changing clothes. After the solitude and quiet of the mountains, I feel a little overwhelmed by the noise and bustle. I take some more pasta and find a place to sit. Here we also get access to our drop bag, which I’d packed in advance with spare shoes, all kinds of clothes and food. In the end, I only change my t-shirt but leave all the other items in my drop bag untouched. It’s now 10.48am and time I was on my way.

I say goodbye to Carrie and the boys and find my way through the street of Courmayeur. The course goes upwards, first along busy roads, then a quiet country lane and eventually returning to the trails. We would now have to regain all the elevation we lost descending into Courmayeur. The climb is long and arduous and I’m thankful to eventually reach Refuge Bertone. The checkpoints on UTMB broadly fall into two categories – the large marquee style checkpoints with rows and rows of tables, benches and crew access and the smaller more intimate mountain refuges. These are mountain huts and are still open to the public during the race. The next section again constitutes a slightly “flatter” section of the course and I try to gain a little time on the runnable grassy ledge between Refuge Berone and Refuge Bonatti. By the time I reach Bonatti, the weather has turned and the warm sunshine has been replaced with a cold wind. After sitting for a few minutes outside Refuge Bonatti, it begins to rain. A cold icy rain. I rush into the Refuge itself in the hope of perhaps finding a quiet corner to sleep for a few minutes. I soon give up on that idea and instead change into my waterproofs.

The descent into Arnouvaz is long and muddy and I’m moving painfully slowly. Other runners are flying down here and ending up on their rear ends in the mud every few metres. Content to stay on my feet, I continue tentatively down. I can see the checkpoint from some way away and I can also see the minibuses behind ready to whisk away any runners who want to call it a day or who are timed out of the race. For the first time, my mind lingers on the idea of dropping from the race. We are well into the afternoon and fast approaching the Saturday night – my second night without sleep. In terms of the big climbs – I have done five but still have another five remaining. The next is the climb to the highest point on the course. It doesn’t seem possible that I can manage that let along another four after that. Surely I should just cut my losses now and save myself the pain? These were the thoughts occupying my mind as I approached the Arnouvaz checkpoint. My mind cannot fathom how I could possibly make it to the finish. But it occurs to me – I don’t need to worry about the finish, I only need to focus on reaching the next checkpoint. Then the one after that. And so on. Eventually the finish will take care of itself.

It takes a massive effort, but I walk past the “abandonment” desk and into the checkpoint proper. I look at the food on offer but nothing appeals so I sit on a bench, with my head on the table hoping for perhaps a few minutes of sleep. However the checkpoint is cold, my clothes are damp and I’m soon shivering. Fortunately, I know just the thing to warm me up, a 738m climb up to Grand Col Ferret! I pull out a packet of Harribo to eat on the way up; it’s about the only thing I can stomach at the moment.

This climb is tough, right from the start and the effort forces me to take regular breaks all the way up. The higher I get the more frequent the breaks. My training for this race has left me in the best shape of my life so I’m initially a little perplexed by how this climb can be taking so much out of me. Then I realise – the vast majority of my training has taken place well below 500m. I had one weekend on Snowdon which goes to a little over 1,000m. Here I am at 2,500 meters and, whilst this isn’t much higher than a high altitude ski-run, my body is simply not prepared for exerting this sort of effort at this altitude. I feel slightly better that my frequent breaks (now practically after every switch back) are down to the altitude and not a lack of fitness.

Soon, we are in the clouds again and there is snow on the ground. The icy wind makes it feel very unpleasant. On the final approach to the pass, I sit down in the snow, completely out of breath. A woman passes by and encourages me to keep moving. She’s right, it’s not sensible to linger here in the cold. We were warned at the start not to rest on top of the mountains but instead to get down to lower altitudes as soon as possible.

On reaching the top, I peer down the other side and my mood lifts slightly. Against all odds, I’ve reached Switzerland.

Switzerland to France

The descent is less demanding than the previous one and I shuffle along listening to some music.

For a long time, I think I can hear the sounds of cow bells at the next checkpoint. I eventually decide that these are cowbells from actual cows grazing nearby as the next checkpoint takes a very long time to materialise. It is situated in the pretty little Swiss mountain town of La Foully. After a steep descent, I chat to another English runner as we approach the checkpoint in the failing light. On leaving, it’s now dark and raining. I put my head torch on which lights up the rain drops like millions of miniature shooting stars in the night sky.

The next section is through the town on roads. One moment, I’m shuffling along and the next I am asleep on my feet, crashing into a barrier on a bridge across a stream. If I’m like this on the mountain, the consequences could be severe! In the slightly surreal space between waking and sleeping, I’ve completely forgotten where I am and what I’m doing. For a moment, I think I’ve been sent out by Carrie to buy pizza for the boys – I wonder what type they would like? Wait no, that’s not right, there’s runners around me. Are we all going up the mountain to see our friend who lives in a house up there? No, that’s also not right. It is a monumental effort to remind myself that I am in fact in a mountain ultramarathon. This pattern repeats a few times as I struggle to stay awake. I think about stopping for a 10 minute doze under a hedge or something but it is pouring with rain so I continue on.

A little later I catch up to an English runner. I am not feeling sociable in the slightest but realise that some light conversation might be my best bet at staying wake.

The extreme sleepiness passes as we begin the climb up to Champax Lac. Although not a steep climb, this section goes on for a long time ascending through forest trails. Mentally, I hadn’t prepared for this being a difficult section and I find myself struggling. During the day on fresh legs, I’m sure it is a stunning hike. But late on Saturday night into my second night without sleep I find my enthusiasm waning. Eventually we reach Champex Lac where there is another checkpoint. It’s now 00:30 and the cut off here is 02:00. Could be worse. The checkpoint is close to the famous lake but between my sleepiness and the darkness, I can see very little of it.

The next section contains some enjoyable downhill running and some very moderate uphill. From the profile, I know we are due a big climb very shortly. We eventually reach the foot of the mountain and I can see long trails of headtorches snaking far far above me into the inky black sky. There are some logs on the ground and a few runners have stopped to sit, fiddling with their kit, changing clothes or just mentally preparing themselves for what’s to come. I join them for a moment before beginning the ascent. Switch back after switch back, this section goes on and on. I recall talking to a few runners but I’ve no idea who or what I said. I have a vague recollection of talking to an Australian runner. Either that or I was listening to Men at Work’s “Down Under” on my ipod!

I eventually see what I have to believe is the final switch back leading to the top only to round a corner and see head torches continuing for what must be another mile above me. Eventually arriving at the actual summit, I can see lights of a town far below me, this might be Trient and our next destination. There is a small checkpoint in an old mountain barn on the way down, really just to scan numbers. There is a sign saying that Trient is only 5km away. Some volunteers have lit a bonfire out back and are warming themselves beside it. For a moment I fantasize about sitting by that bonfire myself dozing in the warmth without a care in the world. Not today! Somewhere on this descent, night begins to give way to early morning and as I emerge from a forest trail, I can see a few buildings ahead of me. It is completely silent but I have to believe that one of these is the Trient checkpoint. My spirits fall further when I realise the trail turns and continues down a farm track. Surely the checkpoint is just at the end of this track? We are directed off the track and onto another series of switch backs through some words. The checkpoint must be here somewhere just through the trees? After several switch backs, I eventually catch sight of the checkpoint, still a long way below me. That 5km sign further up the mountain was a horrible lie!

Dragging myself into the checkpoint, I study the profile of the remaining part of the course. The next mountain looks pretty much a carbon copy of the last one. I don’t have it in me to do another mountain like that last one. I decide that I need to find someone who is familiar with the course who can tell me that the profile is wrong and the next mountain is in fact much easier than the last one. There is an English UTMB official standing close by and I ask her this question. She looks at me and shakes her head sadly. However, she is keen to encourage me.

“It normally takes two hours to get from here to Vallorcine. That’s on fresh legs, However, you have four hours to do it in to make the cut-off at Vallorcine.”

Something in my mind clicks. Ok, if I can get to Vallorcine in three hours, that would give me an hour buffer against the cut-off at that point. With just one mountain left and less than 20km to the finish, I think that would be enough.

I jog out of the aid station feeling optimistic and begin the next climb. It’s now 07:15 on Sunday morning. As I start the climb up to Les Tseppes, I feel my confidence returning and I’m enjoying myself for the first time in nearly 24 hours. I start passing other runners on this climb. This makes a pleasant change as the race to date has been one long procession of people passing me. I think back to my training on Snowdon, running up and down the mountain; this is what I was preparing for though I probably didn’t even realise it at the time. For the first time the finish line, though still many hours away, becomes something tangible and attainable. I power my way to the top and rest for a moment or two, soaking in the views which are breathtaking.

I’m happy to invest a few moments resting here, but I can’t stay long. As much as I like to think of myself as a master tactician playing a game of “cut-off chess”, I realise that “cut-off Russian roulette” is a better analogy. I check my phone. Tim has sent me a message telling me that I can make the finish, but I need to keep moving. I take this advice to heart and begin the descent back down into France.

Return to Chamonix

I have made excellent time on the last ascent and I had hoped to capitalise on this with a fast descent into Vallorcine. However, this isn’t to be. The trail down hill is rutted grass and mud and, again, try as I might I just can’t get a decent pace going.

Eventually I arrive in Vallorcine, exactly on schedule three hours after having left Trient, with my one hour buffer against cut-off intact. I sit for a moment or two in the marquee as crew members rush around looking after their runners. A man announces in English over the PA system that anyone intending to continue in the race should think about leaving soon. I don’t need telling twice.

The next couple of miles are on a grassy trail beside a road. Cars pass by beeping their horns whilst the occupants yell encouragement at us. As I reach the car park at Col des Montets, top British ultra runner, Robbie Britton (who isn’t in the race but is supporting) comes up to me to offer encouragement and a few tips on tackling the next section of the course. I thank him gratefully and start the ascent up to La Flegere.

At this point, the course would ordinarily ascend Tete aux Vents directly, before dropping down into La Flegere. However, this is the second safety modification to the course and so we approach La Flegere slightly differently.

Having been very careful in treating the course with the respect that it deserves so far, at this point, I’m guilty of underestimating the next section. It’s a mistake that nearly costs me dearly. Earlier in the week, I had recce’d the final part of the course, from Chamonix to La Flegere and back down again. This had taken me around two hours and I had found very straight forward at the time. Clearly that was on fresh legs and we are now approaching the mountain from a different side, but I felt that my recce should provide a good benchmark of what to expect. I just need to nip up to La Flegere, then run back down to the finish in Chamonix and pick up my gilet and a cold beer. But the mountains aren’t done with me just yet.

We continue up and up. I recall La Flegere is a ski resort with a lift at the top. According to my calculations, it should be coming into view anytime now. A hiking sign appears for La Flegere directing hikers off to the right. But the race signage is clearly directing us to the left towards Argentiere. I don’t like this at all but there is no question that we are supposed to turn left here. The trail continues along before dropping down sharply. We lose most of the height that we have just climbed. If there’s one thing I recall about La Flegere it’s that it’s at the top of a mountain not the bottom – why are we descending? The trail continues along, traversing the side of the mountain before going up again. I chat to an Irish lady. We trade war stories about the night just passed and rue the lack of large mountains back home in Ireland and the UK for us to train on. I look at my watch and work out how much time I have until the cut-off at La Flegere. Two hours becomes 90 minutes becomes one hour becomes 45 minutes – where on earth is La Flegere?!

At this point, my high spirits have gone. I’m sorry to say that my language turns the air blue though fortunately I don’t think that the grasp of English of my fellow runners is good enough to understand what I’m saying.

Eventually the forest trail opens out onto a wide ski run. I look around desperately searching for the checkpoint – it’s nowhere to be seen. All I can see is a long line of runners continuing up to the very top of the mountain. I completely lose it at this point and start ranting and raving at the nearest runner. A very confused German lady turns and says “Bitte?”. I repeat my rant a little more slowly for her. I state how totally and absolutely unreasonable it is for the organisers to send us on a convoluted route up the mountain. Do they not realise that we have been running up and down mountains for two straight days – all we now want is to go back to Chamonix and enjoy the finish line. The German lady smiles sympathetically and continues on her way.

Of course, I realise deep down that I am the one being unreasonable. No-one has forced me to do this race, quite the opposite. And the route, even the amended one, was available for us to study in advance. I simply made an erroneous assumption about this final section. When a vast chasm emerged between the reality of this final section of the race and my expectation of it, my sleep deprived mind no longer had the tools to be able to deal with it rationally.

I finally reach the top, now only 30 minutes ahead of the cut off here. I look at the food table. This is the final checkpoint and anything I take here will need to last me to the finish. I swig some coke and take some chocolate for the descent. The initial descent on a wide piste must be a delight to ski in winter. Today it is sheer torture. The piste ends and we are on the final switch backs through woods that will lead us back to Chamonix. I’m on familiar ground now. Very rocky, uneven ground. A few days ago, the rocks had caused me no problems, as I sailed over them, laughing and jumping. Now, I can barely lift my feet a couple of inches off the ground. Each rock needs to be negotiated individually, requiring my full attention. I pass lots of hikers who congratulate and encourage me. I smile as best as I can and mumble “merci”.

A lady from Milton Keynes who is supporting other friends in the race jogs alongside me for a moment or two, offering encouragement, before disappearing up the mountain to find her friends. The trail is narrow in places and at one point leads directly across the terrace of a mountain restaurant. The terrace applauds as I pass by. The support is really touching and I can feel my bad mood from earlier melting away.

In my mind, I tick off the landmarks on this final section; the large wet rocks that need careful negotiating, the signpost directing us to Chamonix and finally the small stream crossing our path. A few hundred metres on, the trail gives way to asphalt and I am on the outskirts of Chamonix. An Italian runner is beside me and we congratulate each other in the few words we know of each others’ language before continuing on towards the finish separately. These outer streets are deserted as the whole of Chamonix has seemingly headed towards the finish. Ahead of me I see the metal barriers that will direct me home. Tim calls my name. He tells me that there is quite a reception waiting for me, just around the corner. I could hear the noise from the finish from some way away and it now gets steadily louder. I see Caroline and she thrusts a union jack into my hands. Sam, having finished earlier that day, is there too next to Tim’s family. Finishing the race with my family and friends, old and new, is very special. Putting the flag around my shoulders, the boys join me for the final few metres. Jamie, seeing the chance to beat his daddy at running, sprints directly for the finish line, leaving me in his dust. Nice! I manage to grab hold of Alex’s hand before he gets similar ideas and we jog the last few metres together beneath the famous arch and across the line together.

It’s over. 45 hours, 41 minutes and 4 seconds after leaving Chamonix, I am back. Physically this race has taken me to places of wonder and beauty. Emotionally it has taken me to some places I don’t ever want to return to. As I make me way through the crowds, I try to process everything that’s happened. A lifetime of emotions squeezed into two days.

So the question – was it all worth it? The last two days have contained some of the best moments of my life and some of the most challenging. But as I look back, I realise that without those moments of despair and pain, I would never have felt the moments of elation so keenly. This race was perfect and I wouldn’t change a thing about it.